End of the Road: Marrakesh, Essaouira, and Taroudant, Morocco

- mkap23

- Aug 2, 2020

- 14 min read

Every now and then, we receive a text from Abdel, our Berber mountain host from a remote village outside of Taroudant:

“Salut, comment ça va en Amérique c grave!!!! Prenais soin de vous et votre famille on se verra si dieu le veux .”

Which roughly translates to: “Hi, how is it going in America, is serious!!!! Take care of you and your family, we will see each other again God willing.”

His texts trigger a flood of memories from a trip that now—looking out a small window in an apartment back home in San Francisco, with an uncontrolled pandemic outside—feels almost as if it never happened. While we knew that the trip had to end at some point, the abruptness of boarding an emergency flight to London a little over a week after arriving in North Africa did not allow us to fully process the end of our journey.

Like a distant mirage in the scraggy desert of the Maghreb, our year-long trip still appeared visible when we landed in Morocco. Surprisingly, we had no issues arriving into the country from coronavirus-stricken Europe. With only a handful of known COVID-19 cases in Morocco at the time, we were hopeful that we would have at least a few weeks to enjoy the fascinating country, while figuring out our next steps as global travel began to shut down. But it turned out that Morocco was not an oasis of calm in the coronavirus sandstorm. Just as the camel caravans crossed the Sahara from Timbuktu and ended here, our journey would also end in the Kingdom of Morocco.

Marrakesh

Our first stop in Morocco was Marrakesh. As was typical when arriving in a new country, one of the first things we did was purchase a SIM card. Normally, this is no problem and happens in a matter of minutes, but this time proved more difficult. After struggling to get Karen’s phone connected with the new card, the helpful young man working the Maroc Telecom booth finally stated that the SIM card was sick. We both looked at him with a smile, thinking this was just another funny English translation fail wherein he meant to say the card wasn’t working. Sensing that we didn’t get it, he then showed us the box of SIM cards, and pointed to the fine print on the side: “Made in Wuhan, China.” “It’s sick, it has coronavirus,” he repeated. Too soon, we thought, but we laughed along with him. He eventually got the card to work, by giving it Hydroxychloroquine. (Come on, that doesn't work, he just gave us a new card.)

SIM cards are about the only thing not made in Marrakesh. As a key trading post on the caravan route from sub-Saharan Africa, the city has a long history of entrepreneurship. The ancient city’s souks, located inside ramparts built a thousand years ago, are packed with vendors and artisans. Down the narrow, winding, cobblestone alleys of the Medina (the Old City), we walked by tanneries, metalwork shops, woodworkers, basket weavers, potters, spice shops, Berber rug stores, and of course, the occasional goat carcass. Men (and we do mean just men, as we barely ever saw local women out in public, and when we did, they were almost always over 75 years old)—many fully-clothed in the djellaba, the traditional long robe worn throughout Maghreb North Africa—played the role of both merchant and manufacturer, as many of the small shops sold and produced the goods in-house. At one tannery where Karen ultimately purchased a leather purse, we ventured into the attic to look at more goods, and watched as three tanners quietly crafted the belts, purses, and wall-hangings displayed down in the shop below. It was fun to get lost wandering the Medina’s narrow lanes, ducking our heads under low-flung archways and pushing our way through the maze of alleys, with sunlight filtering through the makeshift ceilings. As we made our way from souk to souk, we spied cow hides drying out in the desert sun as we dodged donkeys hauling carts filled with fruit, making their way incongruously through the lamp souk. Marrakesh is one of the liveliest ancient cities we have ever visited. Uzbekistan’s Silk Road cities may have more historically significant architecture, but it is Marrakesh that still lives its history to this day.

That’s not to say there wasn’t some amazing architecture. The city’s historical wealth, created from being a key trading post on the caravan routes, did have some architectural influence, which was showcased brilliantly at the Saadian Tombs. The Saadians were a dynasty who reestablished Marrakesh to its former glory in the 16th century. Their necropolis, secretly tucked away behind the Kasbah Mosque, opens up into a beautiful courtyard with a handful of tombs on its edges. The tombs feature impressive engraved woodwork on the vaulted entryways, with shiny marble tombs and detailed tilework inside. Amongst all this exquisite art sculpted by hand, we ended up spending most time with…the resident cat, guardian of the tombs. Marrakesh, and Morocco in general, had ample cats roaming around everywhere, and we were not complaining. (Was this a sign that we would soon be going home to our own furry feline back home?)

Down the road from the Saadian Tombs, through an imposing gate, is the Mellah, a walled neighborhood/ghetto once home to the Jews of Marrakesh. The Mellah is strategically located directly next to the Kasbah, the King’s palace. Since the Jews were an integral part of the trading industry that made the kingdom rich, they were afforded protection by the King…or they were kept under locked guard and weren’t allowed to leave, depending on who you ask. Either way, we were told that everyone got along. At one point, there were hundreds of thousands of Jews living in Morocco, though only about 10,000 remain today. Inside the walls of the community was a synagogue that functions as a museum today (with an interesting display of photographs of Moroccan Jews), as well as a very large Jewish cemetery—a testimony to the sizable community that once lived there. Like in the Medina, we enjoyed getting lost in the Mellah’s very narrow lanes, with some just barely a few feet wide. But as it got dark, the old tales of a locked down Mellah began creeping into our thoughts, so we made our way out of the gates and back toward the bustling Medina.

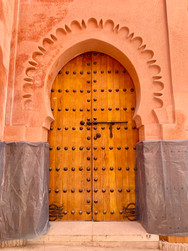

We soon learned that it’s actually quite easy to get lost in most of Marrakesh, or even in most of Morocco in general, because the old cities resemble a maze of tall walls, such that it’s hard to pinpoint a visible distinguishing marker. High partitions tower over the thin but congested pedestrian lanes below them, revealing little of the contents behind the walls. The only evidence of what lies beyond can be seen in the subtle details of the doors—Morocco is a collage of brilliantly decorated portals and doorways overlaid onto blank canvases of mud walls. Upon entry through them via a secret password (okay, not really), one typically enters into a riad, a traditional Moroccan house or palace centered around a garden courtyard, many of which have been converted to guesthouses for tourists these days. The riad that we stayed in featured opulent Islamic carvings, Arabian Nights-like archways and lamps, and desert plants. Like many other riads, it is designed to stay cool in the desert heat, leveraging functional and beautiful design elements like outdoor breezeways, marble flooring, and a façade painted in reflective white. Thankfully, since we were visiting in March, we did not experience the intense heat that comes during the arid summer months. In fact, the weather was quite pleasant for our week in the country. At breakfast—which included a delicious spread of fresh pastries (the riad, like many in Morocco, is French-owned, hence the pastries) paired with meat and eggs cooked in traditional tajine pots, fresh yogurt with fruit, amazing orange juice, and Moroccan mint tea, served on the roof deck each morning—we would actually maneuver ourselves to stay in the sun’s rays to keep warm, as the desert mornings were actually downright frigid. But then, as the sun began to intensify, we quickly had to seek shelter in the shade. In some ways, we felt like we were cold-blooded animals, moving from the sun to the shade to stay either warm or cool, depending on the state of our own body temperature.

The riads provide shelter from the heat, the dusty streets, and the hustle bustle of the Medina, but they also gave Europeans, especially those hailing from the former colonizing countries of France and Spain, the opportunity to move to Morocco while feeling right at home. We could feel this at the Museum of the Confluences, another beautifully restored riad located down the street from our guesthouse. Despite the museum’s main purpose to showcase art from the various cultures of Morocco and across the Islamic and African world, it was the European influence on Morocco that really shined through. An exhibit on Yves Saint Laurent, who made his home in Marrakesh for many years, displayed some of his Moroccan-influenced fashion, while a seemingly random (yet delightful) Parisian-style coffee shop pumped out fantastic coffee-roasting aromas throughout the courtyard (not to mention an impressive menu of hundreds of different coffees!). In fact, it seemed like more visitors came to check out this Euro coffee shop than the Islamic art.

We had a similar experience at the ANIMA Garden. After a delicious and heaping lunch on cous cous Friday (real traditional cous cous is only cooked and served on Fridays, since it takes so long to make; we shared one massive plate filled with chicken and veggies for only $2), we headed out toward the foothills of the beautiful snowcapped Atlas Mountains to this art park. Created by Austrian artist André Heller, the park featured vibrant unique gardens with even more impressive sculptures, including works from Keith Haring and Picasso, as well as intriguing modernist pieces. But as far as we could tell, there was no local art there. Morocco may be the transition between Europe and Africa, but these sites clearly leaned toward European sentiments. However, we did get an appreciation for local design at Le Jardin Secret in the Medina (the Secret Garden, which is not secret at all, as it is highly recommended on every tourist map). Le Jardin Secret is an old riad featuring two open courtyard gardens in traditional Islamic design and symmetry; most interesting of all (to us, at least), it showcases and keeps intact the old underground water system called a khettara, perfectly engineered to bring fresh water all the way from the Atlas Mountains into the city through a series of carefully laid clay pipes over long distances that take advantage of gravity and natural pressure-building methods to bring water to the gardens and the people.

On our last night in Marrakesh, we took part in the craziness that is Jemaa el-Fnaa Square. Over a scrumptious dinner at a food stall that served up tajine lamb, barbeque skewers, and exquisite roasted eggplant (as well as delicious orange juice, per usual and probably our fifth glass of the day), we watched as numerous crowds formed around drum circles, card games, magic tricks, and other vaudeville musical acts. Though tourists can participate—for a small fee, of course—this lively affair is mostly attended by locals. One could almost sense that these activities had been passed down over generations, with merchants gathering in the square for some much earned entertainment after their long journey to reach the trading post. Everybody was living it up and having a great time, getting lost in the moment. Unfortunately, it would be the last night to do so.

Like the narrow lanes of the Medina, the travel world began to slowly close in on us and became a maze of confusion. We woke up the next morning to learn that Morocco had banned flights from over 25 countries, mostly from Europe, but also those to our next intended destinations, Tunisia and Egypt. With this news, the few tourists that were still in Morocco began to scramble to get out of the country. Our riad emptied out; the French guy who had been with us at the gardens rushed out to Agadir at 4:30am to catch the last available commercial flight back to France. That, combined with the souks being closed for the weekend, made the city feel eerily quiet after it had just been bustling the night before. Meanwhile, with our next destination after Morocco suddenly unclear, we continued on within the country’s borders, boarding a bus bound for the Atlantic Coast and making the three-hour journey to the ancient port city of Essaouira.

Essaouira

We tried to make the best of our time in Essaouira, even though we spent most of it trying to get out of there. While flights to the U.S. had not yet been canceled (it was only mid-March), we knew it was only a matter of time before that, too, would happen, and all other countries would be locked down. Knowing our end date was imminent, and with a surreal sense of both longing to continue and longing to go home, we went out exploring.

Essaouira is a cold, semi-rundown city, wind-swept by the howling, unrelenting gales coming off the Atlantic, which didn’t help improve our mood. We sluggishly walked through the blue and white colored Medina, visiting the pungent fish bazaar and dodging some pushy argan oil dealers. At the southern tip of the old city, the seagulls circle above the fresh fish market, hopeful for their next catch; we did the same, hovering around a strip of fish stalls near the Citadel, trying to assess the best deal, before putting down 100 Dirham (~$10 USD) for a large platter of grilled fish and assorted seafood. After stuffing our faces while debating the increasingly limited options for our next steps, we took a long walk on the beach, dipping our feet into the cold water, watching it wash away our footprints along with the lightness in our hearts. At the far end of the crescent-shaped bay, we tried to lift our spirits with camels, but riding the camels in circles around the beach, as if we were five-year-olds at the local zoo, was a poor substitute for the camel trekking we were supposed to do in the Sahara the following week. Toward the end of the day, we walked through Essaouira’s Mellah, then climbed up onto the city’s massive coastal ramparts, watching the sun set on our trip as we stared across the Atlantic toward home.

When we returned to our riad that night, we begrudgingly booked the next affordable flight home that we could find, which was a week later on March 22nd—hoping that the world would grant us at least that much more time before it shut down completely. It did not. Shortly after we booked the flight, we learned that all flights in and out of the country had just been shut down (not just those to and from Europe), including the one we had just booked. We called the U.S. Embassy to see what to do, and they told us to sit tight for a few days while they figured it out. With all the Europeans gone, the U.S. Embassy silent, and Morocco taking steps toward a military-enforced shelter-in-place in just a couple days, it was no longer enjoyable to have the country to ourselves, as it felt eerily post-apocalyptic. For both nights in Essaouira, we ate at very good restaurants where we were the only customers. As Morocco no longer wanted us there, but also wouldn’t let us leave, for the first time in all our travels, we felt alone.

Taroudant, Imoulass, and the High Atlas Mountains

The next day, we decided to try our luck in Taroudant, a small town six hours southeast of Essaouira—not because we thought the situation would be much better, but because we had already booked a place to stay there that was non-refundable (still on a backpacker budget!). Taroudant is supposed to be a fun place to explore an authentic Medina, as it is considered a mini-Marrakesh without the tourists. As it turned out, we would have preferred the crowds, as nothing was open. With restaurants already shuttered by new government orders, we were forced to eat all our meals at our guesthouse. And since we were the only ones staying at our guesthouse, we unfortunately had the undivided attention of the proprietor, Yves. It was immediately clear to us how a French guy ended up owning a guesthouse in this remote desert oasis town—he was crazy. He subjected us to bad French rock at high volumes, as he drunkenly sang along. He scared the shit out of us with tales about how we were the last tourists left in Taroudant and how we were going to be stuck in Morocco forever. We weren’t scared about getting stuck in Morocco; we were scared about getting stuck in Morocco with him.

However, despite his madness, Yves was generous, arranged good meals for us, and did introduce us to a great ambassador for the country, his friend Abdel. Born in a remote village in the High Atlas Mountains a few hours north of Taroudant, Abdel is a Berber who grew up in Belgium, where his parents worked in the mines. Because of this, he spoke numerous languages, though English was not one of them. Through Google Translate in French, Abdel guided us into the mountains above his hometown of Imoulass, giving us a glimpse into the life of a Berber herder. We followed along on goat trails across the dry, craggy hillside, with epic views of the towering Atlas above and the vibrant green Mediterranean valleys below. Once again, we felt alone, but this time it was by choice, which allowed us to relax a bit and clear our heads. Standing high atop the peaks with little around us, breathing in the mountain air, we felt tranquil and all of our problems felt small before the immensity of the mountains. After our day hike with Abdel, we went back to his house, where we spent the evening playing with his sheep, rabbits, and chickens, and eating another large plate of chicken cous cous, which his wife cooked for us. Abdel’s warm hospitality, not to mention his knowledge of the current shelter-in-place situation, was one of the only bright spots of our time in Morocco (that this herder from a remote Berber village knew more about what was going on than the U.S. Embassy was an insightful look into the current state of the U.S. State Department).

Did we mention Yves was crazy? When we got back to Taroudant the next day, we decided that we wanted to at least see what Taroudant looked like, rather than be cooped up inside with him all day. So we went biking around town with him, though it didn’t prove much better. Yves’ bike was equipped with a loudspeaker, enabling him to blast music as we cruised the city, drawing the glares of locals already wary of Europeans who brought in the coronavirus from across the Mediterranean. Our two borrowed bikes were no less conspicuous, decked out with the flags of the U.S. and EU, flapping in the wind behind us as we biked down cobblestone alleys, past the massive town Citadel, and through a completely empty and closed up souk (which was depressing). We didn’t expect that our last activity on this six-month adventure would be playing colonialist, but here we were—foreigners parading through a random town, waving the Stars and Stripes and blasting Whitney Houston. We got some laughs, but we also got a lot of stares and some shouts of “corona!” in our direction, as well as one well-deserved, “get the f out of here!”

Little did that Moroccan teenager know, we were actively trying to get the f out of there. When we got back to the guesthouse, we continued to frantically search again for a flight home, half expecting an angry mob to raid Yves’ place that night. As we mentioned in our “Chased Home” blog, thanks to the British ambassador (and no thanks to the U.S. ambassador, David Fischer, we were finally able to book an emergency flight to London, where we could then catch flights to the States. That night, we packed up our bags in anticipation of our early 5:30am taxi ride to Marrakesh in the morning. What was usually a routine chore that we did almost daily over the past six months suddenly became an object of focus—it would be the last time we’d pack up like this for a while.

Two plane rides, a night spent in London, and about 40 hours later, we landed in Newark, New Jersey, and turned on our U.S. cell phone service. We immediately saw a WhatsApp text from Abdel: “Vous serez toujours les bien venu chez nous.” “You are always welcome here.” While our time in Morocco was soured due to the global pandemic, Abdel’s sentiment reflected the same that we experienced throughout our entire trip. Everywhere we went, we were welcomed as friends or even family. As cliché as it sounds, it was not the places we saw or activities we did that we’ll remember most, but rather, it is the people we met that will always stay with us. We’ve been sad that our trip is over, but we’ve been just as happy and heartened to know that most humans in this world are good—they are out there, ready to feed us and embrace us with open arms. We look forward to giving Morocco another chance, and getting back out to the world one day soon, as this caravan journey doesn’t stop.

Karen & Michael

Marrakesh, Essaouira, Taroudant, Morocco, March 11-19, 2020

Comments